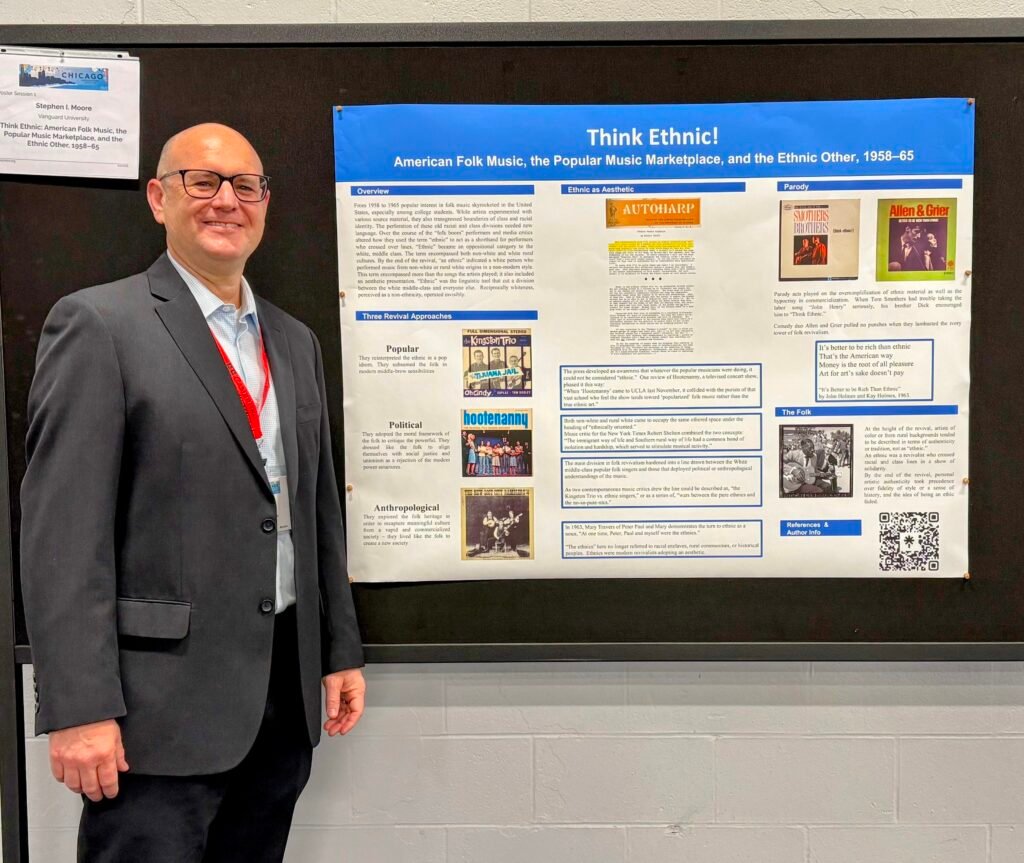

This January I had the privilege of presenting at the American Historical Association’s national conference in Chicago. It was a time when I could share my work with the wider academic community, reacquaint myself with the state of the field, hear from colleagues at peer institutions, meet with publishers to discuss the prospect of turning my dissertation into a book

Poster on the Folk Revival

My poster presentation considered a minor point of my PhD dissertation, which examined the American Folk Revival, 1958 – 1965. I looked at the evolution of the use of the word “ethnic,” which was used to describe the folk revivalists themselves. Those that crossed class and racial boundaries were, for a time, described as “ethnics.” The use of this word to demarcate boundaries crossed in revivalist activities, while it also reinforced the invisibility of the while middle class as a category. That is, the absence of whiteness in the broad understanding of the ethnic, served to affirm its status as invisible default.

The State of Liberal Arts Colleges

The first session I attended focused on governance in small liberal arts colleges. In general, the faculty in attendance came from the colleges struggling with dwindling enrollments and cuts to the humanities. The attendees were most concerned with attracting students and dealing with declining faculty lines. There was a pervasive sense of being asked by administration to do more with less.

We also identified a larger cultural ambivalence with the humanities. Undermined in the public consciousness for a generation, due to a prioritizing of both STEM as the forefront of innovation and Business as the rational ROI, history as an academic pursuit has more recently also been painted as a breeding ground for radical political ideologies which undermine the national project. Consequently, the historians in attendance perceived a diminished academic freedom in the classroom, compounded by the threat of surveillance from the student population themselves. Who knows what stray comment may be recorded in a class setting and uploaded to a rapid band of internet trolls eager to dox their political adversaries and intimidate marginal communities with political violence?

We then considered how we should demonstrate the value of the history degree to an undergraduate predisposed to view it as either a waste of time or a danger? Over the past decade, the answer had been to advertise the marketable skills of the history degree. Analysis, conceptual thinking, and research were all valuable skills for the business world. But this framing buys into the canard that the degree is simply a professional certification. We decided that we must make deeper arguments as to the need to frame the major as an important opportunity to engage with those things that make us human.

In more practical terms, we also discussed ways to publicize the work being done in departments, the “soft” recruiting of students. Social media engagement and informal, casual interactions can help to create a sense of belonging for the students. Creating external constituencies through alumni networks, newsletters or the formation of an advisory board aimed at generating funding can help to subsidize dwindling administrative support. Also, departments viewed interdisciplinary departmental work as a means to bolster support for humanities and social sciences in general through a kind of cross-pollination.

The Library, the Community, and the Individual

I also attended a session that reconceptualized the archive and the library as a tension between the individual and the community. While the work of the library requires creating spaces for embodying the “collective self,” theses spaces must also allow for individual research and intellectual development. In that pursuit, the library’s main job is that of interlocutor not preserver. Presentations in the library that would benefit the university community include forums that prompt collective thinking and collective experiences of intellectual engagement. On the other hand, the library is a site of intellectual “self-determination.” Self-education is required for liberation. Ideally, the library can be a site of experimentation and non-ideological exchange of ideas for the community and the individual.